'Moonlight': Is This the Year's Best Movie?

By: A.O. Scott

October 20, 2016

NYT Critic's Pick

Directed by Barry Jenkins

Drama

R

1h 51m

NYT Critic's Pick

Directed by Barry Jenkins

Drama

R

1h 51m

To describe “Moonlight,” Barry Jenkins's second feature, as a movie about growing up poor, black and gay would be accurate enough. It would also not be wrong to call it a movie about drug abuse, mass incarceration and school violence. But those classifications are also inadequate, so much as to be downright misleading. It would be truer to the mood and spirit of this breathtaking film to say that it's about teaching a child to swim, about cooking a meal for an old friend, about the feeling of sand on skin and the sound of waves on a darkened beach, about first kisses and lingering regrets. Based on the play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue” by Tarell Alvin McCraney, “Moonlight” is both a disarmingly, at times almost unbearably personal film and an urgent social document, a hard look at American reality and a poem written in light, music and vivid human faces.

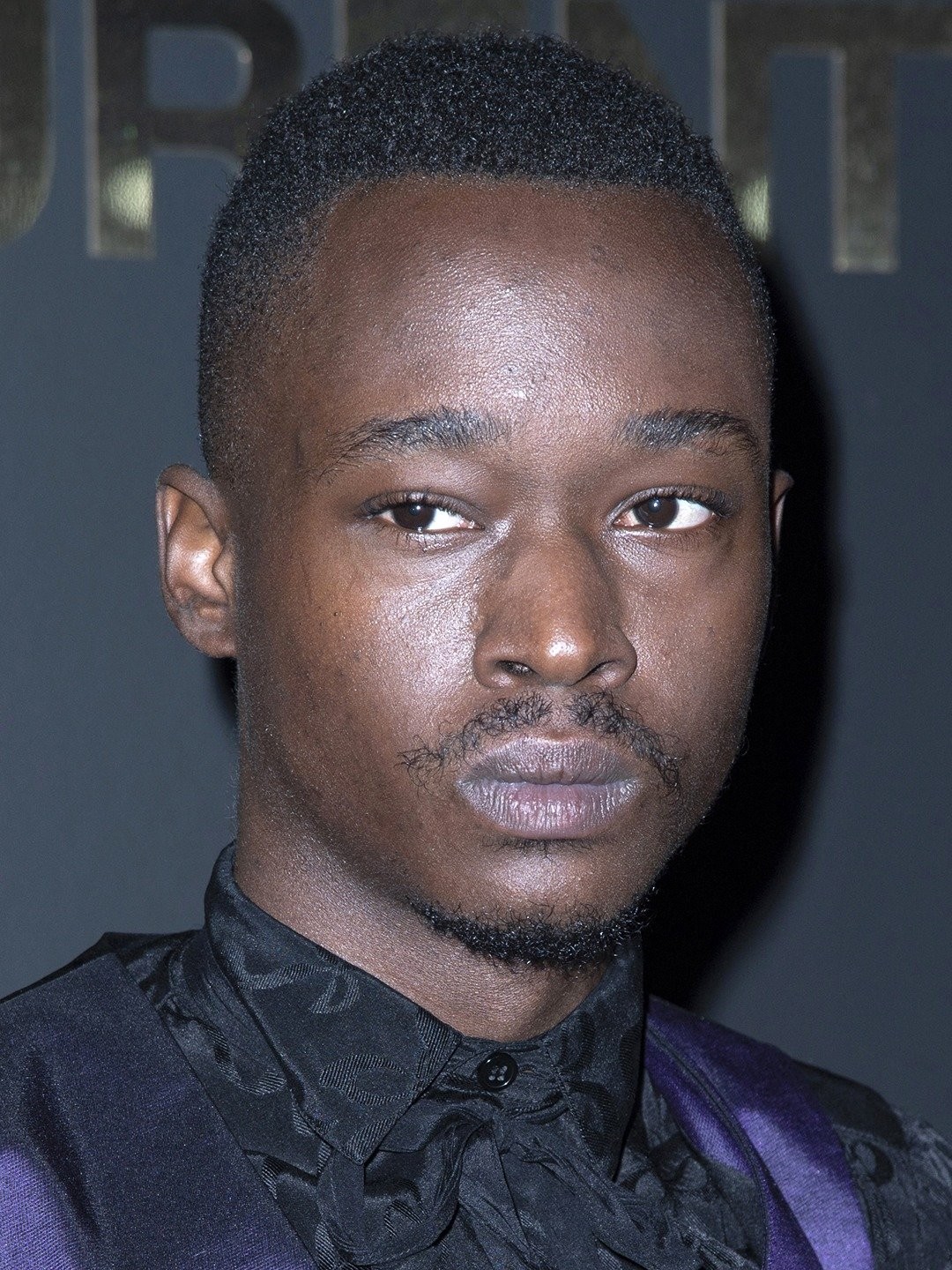

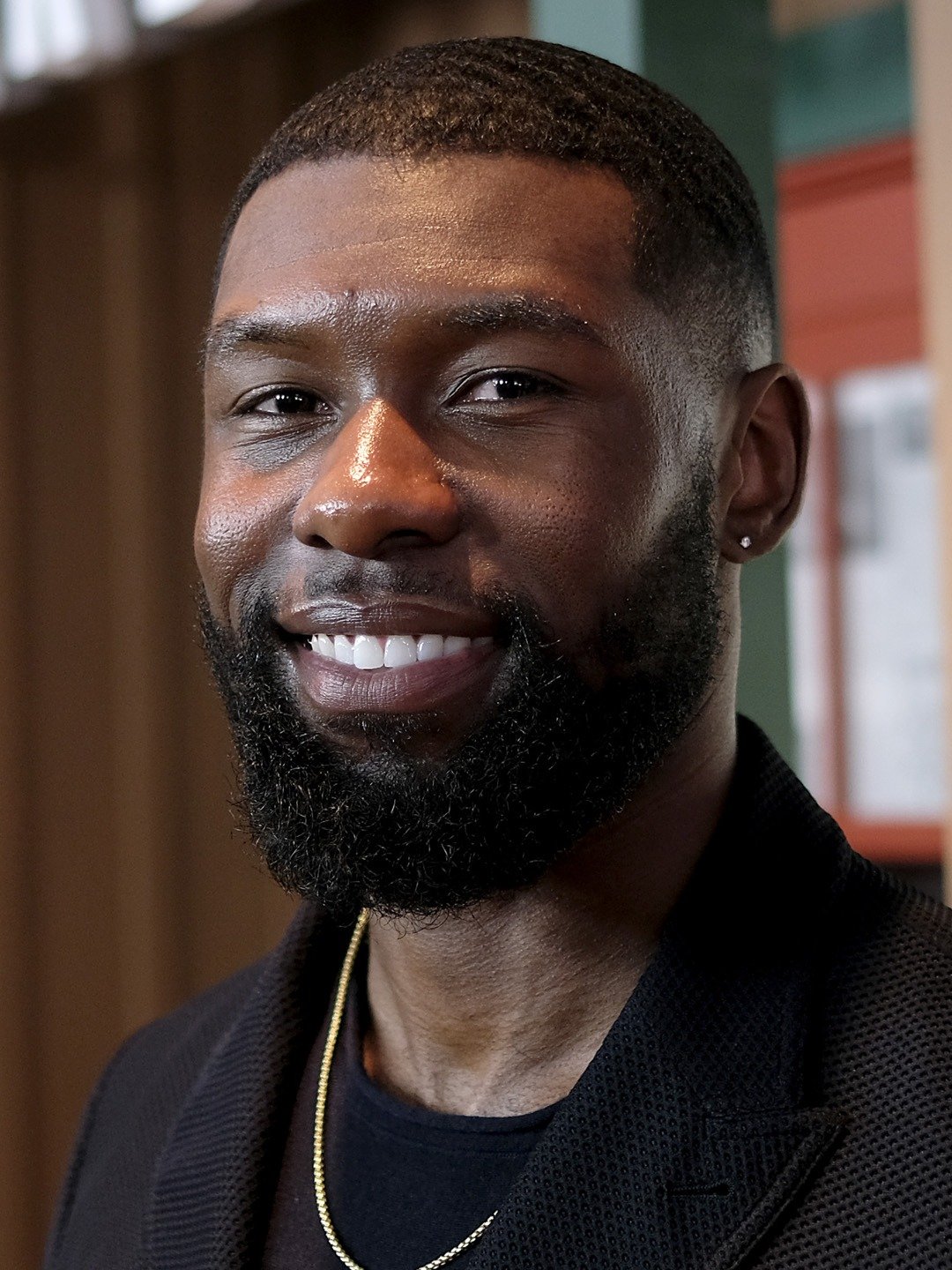

The stanzas consist of three chapters in the life of Chiron, played as a wide-eyed boy by Alex Hibbert, as a brooding adolescent by Ashton Sanders and as a mostly grown man by Trevante Rhodes. The nature and meaning of manhood is one of Mr. Jenkins's chief concerns. How tough are you supposed to be? How cruel? How tender? How brave? And how are you supposed to learn?

Chiron's initiation into such questions seems to be through fear and confusion. We first encounter him on the run, fleeing from a bunch of other kids who want to beat him up. Chiron is smaller than most of them — his humiliating nickname is Little — and vulnerably different in other ways as well.

His effort to understand this difference — to work out the connection between the schoolyard homophobia of his peers and his own confused desires — is one of the tracks along which his episodic chronicle proceeds. Another, equally painful and equally complicated, is Chiron's relationship with his mother, Paula (Naomie Harris), who slides from casual crack smoking into desperate addiction.

The drug trade around the Miami housing project where she and her son live is controlled by Juan (Mahershala Ali), who becomes a kind of surrogate father for Chiron. The tidy, airy house where Juan lives with his girlfriend, Teresa (Janelle Monáe), becomes an oasis of domestic stability, a place with hot meals, clean sheets and easy conversation. (Though for someone who at every stage says as few words as he can, easy is a relative term.) That this comfort is purchased with the coin of his mother's misery is not lost on Chiron. “My mama does drugs?” he asked Juan at the dinner table. “And you sell drugs?” Watching him complete the syllogism in his head, and watching Juan's reaction, is heartbreaking.

But there is much more to “Moonlight” — and to Juan — than this brutal double bind might suggest. The drug dealer as default role model for fatherless youth is a staple of hip-hop mythology, pop sociology and television crime drama. But Juan, like a figure in a Kehinde Wiley painting (and for that matter like Chiron, too, in a later phase of his story) evokes clichés of African-American masculinity in order to shatter them.

-